The Evolution of Technology series continues with The Answering Machine. Professor David E. Weber will largely write this column, with an introduction and closing by me. I have to include a short video of a message that Professor left – years ago – which he probably doesn’t even remember leaving on his answering machine.

It was when the musical “Annie” had first opened on Broadway and its signature song, “Tomorrow,” was literally all over the place. David co-opted that song for his own message, which for reasons I just don’t understand, I remember clearly. Why I remember that and can’t remember someone’s name, phone number, or what I did just yesterday is just one of those life mysteries. My rendition of his message is at the end of the column.

So, without further pre-amble, here are Professor’s Weber’s recollections and thoughts about answering machines:

My first encounter with a telephone answering machine occurred in roughly 1967. I called my classmate Mike one evening. His home phone picked up, and through my receiver came an outgoing message that, at literally two to three minutes long, would seem interminable to us today.

The voice was Stan’s—Mike’s dad. In the earliest years of answering machines, the husband and father—the man of the house—recorded the outgoing messages, a task considered in that era too technically sophisticated for mere women to perform.

Stan enunciated every word—every syllable—meticulously and soberly: “This…is…an…electronic…answering machine…that AUTO-MATIC-‘LY…an-swers the phone…and re-cords…your mess-age for us….We are cur-rent-ly… A-WAY from home…and you…are now list-en-ing…to an AUTO-MATIC…,” blah blah blah. Stan then gave instructions for what to do—“Lis-ten…for…the…beep-ing sound…and then SLOW-LY and DIS-TINCT-LY…CLEARLY state your name…phone num-ber…time and date of your call…and a BRIEF mes-sage,” and so on.

Before Stan’s “good…bye” drifted from the phone in a spooky monotone, he closed by repeating, “This…is…an…electronic…answering machine…that AUTO-MATIC-‘LY…,” and repeated his message short of giving the instructions again. I actually handwrote brief notes—“name,” “time” and the rest—to ensure I would not inadvertently exclude a single vital piece of information Stan had requested. “This…is…DA-VID…WE-BER…,” I intoned, “the time is…EX-ACTLY…se-ven twenty-two…pee-emm…,” and I probably said it all twice.

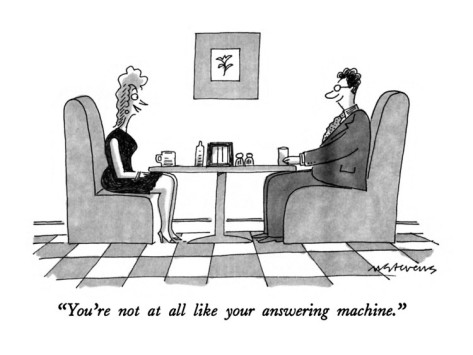

Within ten years, answering machines were not rare. You may recall that by the late 1970s, the trend was to leave “cute” or “clever” outgoing messages that, in retrospect, seldom met even the lowest standards of charm or wit. I hesitate to confess one of mine, but for the sake of illustration: during Thanksgiving season 1978, my outgoing message had me playing the part of a turkey, out of breath, trying to evade the axe wielded by me. I changed my outgoing message every couple of months, not just to coincide with the season but to give me an opportunity to create brief thirty- or forty-five second radio dramas, essentially.

Kenny, a friend and actor, would call simply to leave long, improvised stream-of-consciousness commentaries—all of them hilarious, containing provocative images and ideas you would never think of combining, and all in the poorest taste possible.

By the late 1980s, the devices had become ubiquitous. I once called a colleague and her teenage son picked up, answering dully, “H’lo?” I asked for his mom, who he said had gone out somewhere. I asked if he’d mind taking a message. “Uh, why’n’t you put it on the ans’ring machine,” he proposed, “just call back right away ‘n’ I won’t pick up.” I felt insulted and felt like giving this sociopath a lesson in civility. Yet not too long after that, I would, when a kid answered the phone, routinely suggest, “Why don’t we hang up, I’ll call right back, and leave a message for your mom on the machine.” This actually illustrates how our technology is seldom used solely the way we first designed it. The telephone itself was envisioned by Edison as a device by which people would listen to music, which would be played by an orchestra at the other end of the line (He also unsuccessfully lobbied Americans to answer their phones with “Ahoy!”).

Now, of course, even the term “answering machine” has become outdated. Even landline systems offer voicemail functions that do what an answering machine does. In about 2007 I bought the cordless landline phone I still use at home if I’m not using my mobile phone. It came with a voicemail function built into the base unit, so no need to have purchased a separate answering machine. I suspect that dedicated answering machines will sooner rather than later go the way of cassette recorders, for example: available only in a handful of stores (and of course on eBay!), from only a few manufacturers and in only a couple of models or configurations.

Thanks, Professor Weber. I relate and remember so many similar things about answering machines when we first got them. My cousin Sandy, to this day, still speaks very slowly whenever he leaves a voice message on my cell-phone. It reminds me of the that great scene in “Singin’ In the Rain” when talkies are first introduced at the studio exec’s house and a funny-looking “professor” explains how they work:

Anyway, as promised at the beginning of this column in my introduction, here is my rendition of Professor Weber’s early message on his own answering machine, long before he was a Professor and when “Annie” has just come out: