Professor Weber leads off our look at adding and subtracting – math – and the devices old and new that we employ, in this edition of the Evolution of Technology blog series which is co-written by Professor David E. Weber and myself.

We often use the term technology as a catchall shorthand reference to the microprocessor-driven devices (notebook and desktop computers, mobile telephones and smart phones, tablets, iPods and more) we use for work, play and management of our lives generally. The basic purpose of the chips in the hearts of those devices is to perform calculations. Therefore, to think in terms of the evolution of technology is to a significant extent to think about the evolution in tools used for calculating.

I began counting on my fingers (I have ten), later used rudimentary memory systems to keep count (I remember a second-grade assignment in which we tied one knot on a string to represent five units, as cowboys ostensibly did when counting cattle), and performed and logged calculations with pencil and paper. I believe that today’s youngsters probably do as much. I also used other tools for calculation that Millennials and their younger siblings may never lay hands on.

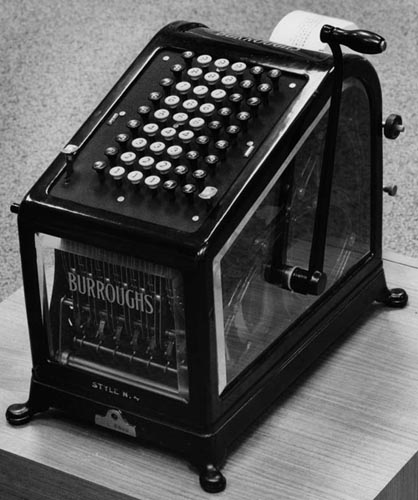

As a child, when I visited my father at his law office, I made straight for the secretaries’ bullpen to play with my favorite device: the adding machine, with a gracefully rounded Bakelite housing, mint-green numeric keys and, rolled neatly like toilet tissue, narrow white paper that curled backward over the rear of the machine. For several minutes, I would type in number after number, some with four or five digits and others with one or two, and then hit a button and get an immediate sum. Magic! I also liked the sound –“sha-ka-zhoozh!” — that the machine made when I mashed the button.

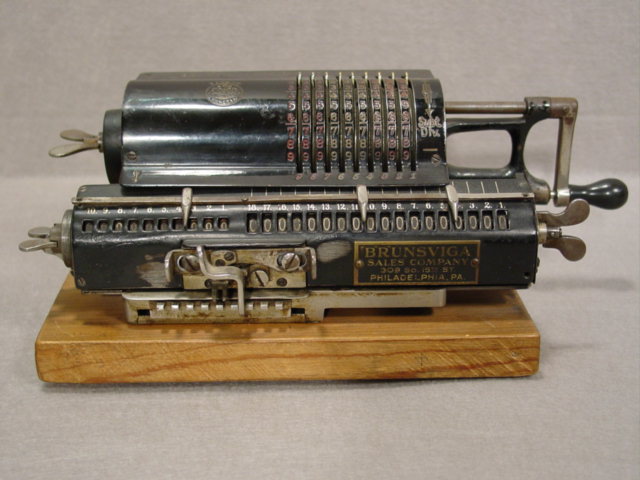

In ninth grade I encountered a new calculating device. My high school purchased a calculator. I don’t mean a hand-held device, though. This “calculator” needed space; so the science teachers moved around lab equipment and furniture to give it, if I recall, about as much square footage as one would allow for a closet. Students in almost all the science and math courses, required or elective, used the calculator for various assignments. You had to make an appointment to interface with the calculator. I remember having to write out the figures I wanted to calculate; I seem to recall I handed my paper to a student volunteer who somehow input the numbers; and I received the results on a piece of paper. How I used those results, though, I don’t recall. All in all, the adding machine was much more fun.

Near the end of high school, though, I encountered a very cool calculating tool: the slide rule. I never liked science or math and did not do well in those subjects, but I loved my slide rule. I could, or needed to, perform only a couple of types of calculations, but what fun to use that “slip stick!”

In the 17th century, a British mathematician named Oughtred built the first tool that we might recognize as a slide rule. It consisted of thin, flat, notched and numbered rods that, laid next to one another, used logarithmic principles to perform accurate calculations. It took two hundred years, though, before a French military engineer invented the runner (e.g., the clear, sliding “window” with the cat’s-whisker, designed to lead your eye to the correct numerals) that would bridge across the rods. In the U.S.A., inventors further refined the design and first began filing patents for “better-mousetrap” versions of slide rules during the second half of the 19th century.

I got my first slide rule — a moderately priced but beautiful bamboo device, manufactured by Post — as an eleventh grader taking (against my will!) chemistry. Slip stick makers favored bamboo because of its stability no matter the weather or humidity (I would occasionally shake a small amount of baby powder onto the tracks, to ensure that the perfectly machined wooden strips might always glide effortlessly as, tongue in groove, they nestled into one another). On the chem. lab wall, our teacher, Mr. Miller, hung a so-called demonstration slide rule, probably eight feet or more long, using it to walk us through the procedures we had to master.

My Post slip stick stayed in a desk drawer in my old bedroom when I went away to college in 1970. I weaseled out of even some required classes in what we would today call the STEM subject areas. I therefore had no need for the bamboo beauty and it disappeared at some point.

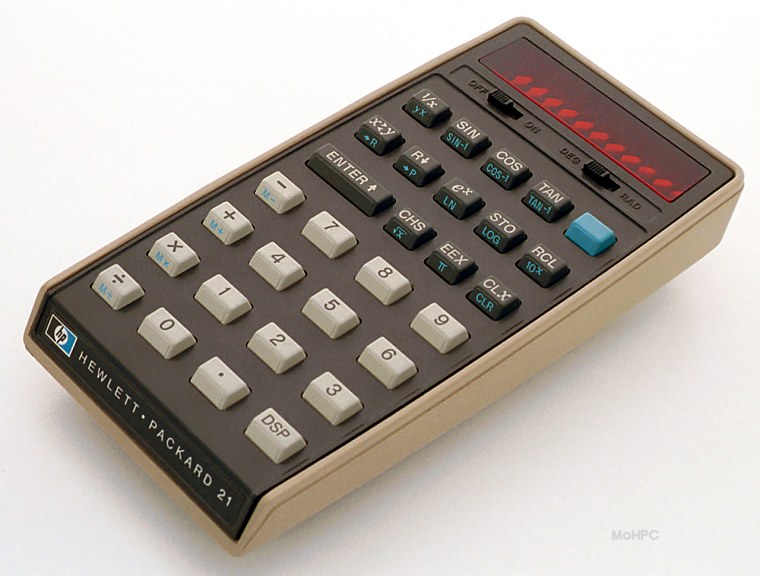

Small electronic calculators knocked slide rules out of the box for good, seemingly overnight. The first of them appeared in the early 1970s. Some people even referred to them as “electronic slide rules.” As a humanities major, I did not need them any more than I needed a slip stick. In fact, from the beginning of college until the late 1980s, when I first purchased a small calculator, I simply used pencil and paper whenever I needed to calculate. Despite not liking math, I nonetheless could always figure quickly and accurately by hand. I figured I would lose those skills if I relied on calculator. Also, I didn’t trust the devices. For as long as several months after I first owned one, I would punch in numbers, hit the equal sign…and then hand-calculate the problem just to make sure the calculator had given me the right answer!

This story ends with the dawn of the home computer age and digital spreadsheets. I never actually learned how to use the spreadsheet application programs, though. Although for several years in the 1980s-‘90s I had a business as a consultant, I successfully sidestepped the mathematics part of running my one-man consulting operation. Today, I use spreadsheets for one of the courses I teach at the university: two hundred students in the course every semester. The first semester (Fall 2009) I taught it, I calculated each student’s grade with my calculator. Talk about drudgery … hours and hours and hours across a couple of days that I will never get back!

The next semester, I asked a computer ops technician to set up an Excel spreadsheet for grading. Inputting the grades for the various assignments and exams takes time; but once you’ve done that, the Excel equations (which I have no idea how to write!) take all the hard calculation work off your shoulders, and you end up with a gorgeous column to the far right of final scores.

Wow, Professor Weber, as usual you astound me with your memory and the details you provide. My memories are a bit sketchier, but I do recall that I was the “party trick” at many of my parent’s dinner parties when I was quite young because of a unique ability I possessed. I was pretty much a human calculator, with the ability to very quickly add, subtract, and multiply pretty large sums very quickly. My parents would proudly parade me out to their guests and ask them to shout out calculations and I invariably would elicit a chorus of “wows.”

Consequently, math was an easy and favorite subject throughout my schooling. I recall seeing slide-rules but never was taught how to use them nor did I need any calculating device during my Psychology major in college.

I recall seeing smaller calculators appear sometime during my undergraduate period, in the early seventies, but they were pretty big and pretty expensive. I still was able to very quickly do most calculations, though not with the whiz speed of my single-digit years.

For much of my life, watches fascinated me so when Casio came out with a digital watch that had a calculator built into it; I thought I was living in the Space Age. Well, in fact I was, since those were the years of major space exploration in our country.

Beyond that, I continued to take pleasure and pride in knowing how to do most calculations very quickly in my head. I learned the basic tricks to speed up the process and I still enjoy showing off when given the chance, plus experience has given me the ability to guestimate (spell check is saying that isn’t a word? I don’t care) pretty darn well.

A related memory that still disturbs me was trying to learn the computer technology of the day that included these foreign languages such as Fortran and others. I never “got it” and struggled with those then required courses. Later, during my MBA, I was required to take statistics and that course really spoke to me and make a ton of uncommon sense since the actual number needed to have reliable statistics doesn’t comport with our instinctual sense.

Later, I used to say that what I learned in that statistics class was the ONLY thing I ever used in my later career in showbiz. I was about the only person who could explain how and why the infamous Neilson television ratings both works and how and why they were accurate to a degree well beyond the sample they used. The reason they used a larger sample was exactly because the real needed one would just defy most people’s understanding. I found that a wonderfully interesting but useless fact.

Okay, that is it for my memories on this topic. Please check out the other columns in our Evolution of Technology series. What do you think of our turning this into a book? My thought is to make it a coffee-table book with an array of very cool photographs? Your thoughts?

How about skipping that $5 Starbucks latte and splurging $2.99 (for the Kindle on Amazon) or $2.79 for the PDF of my new e-book? Enjoy my own informercial for it! This e-book is really a virtual journey. It’s filled with 100 photos, 7 original videos, and links to many of the stops on the trip. Click on the book cover image below to find your purchase options: