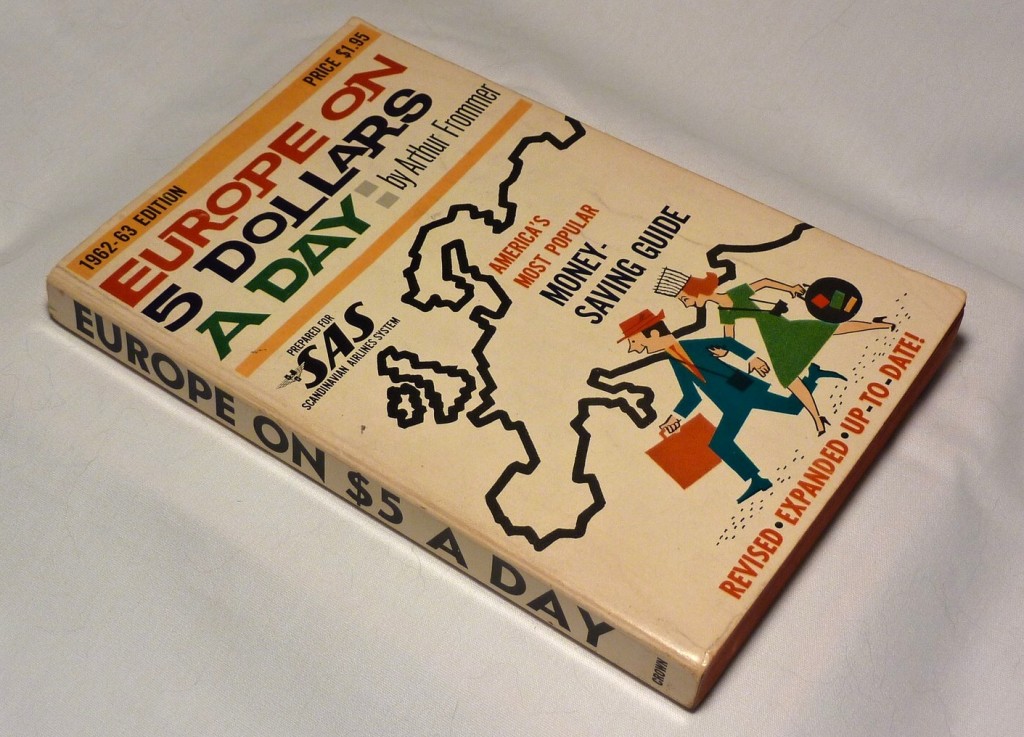

In this edition of the Evolution of Technology blog series, which is co-written by Professor David E. Weber and myself, we take a look at Travel. How we book it, do it, and live it. Without a doubt, travel has undergone incredible changes since I went to Europe using Frommer’s “Europe on $5 and $10 a Day,” when I was 19. And, we did it, too. I’m going to take the first stab at this column, followed Professor David E. Weber who, as I am writing this, is traveling to and from England.

That first big trip to Europe, in the early 1970’s seems, in retrospect, to have truly taken place in another age. Almost everything about that trip is not possible today, besides simply the costs. In those days, Europe was a popular destination simply because it was so cheap (and the American dollar actually had value). That first trip cost less than $1,000 for nine weeks – everything included. Nowadays, you can easily spend $1,000 for s single day in certain major capitals such as London or Paris.

Of course, I went on that first trip as a student. But, my best friend and I were determined not to do what was the popular hostel route of travel, staying in group homes before the word “hostel” was corrupted by a horror movie. We committed to finding inexpensive rooms, eating at least one meal (dinner) out each day, and not backpacking it.

One of our secrets was spending nine nights during those nine weeks sleeping on trains as we went to a destination. Rail passes were cheap for students and given the preponderance of trains and the relative close proximity of European countries, it was and probably still is the travel method of choice.

Our meals were usually the simple continental breakfasts provided at the inexpensive hotels we found. Mostly, we used Frommer’s book and upon arrival in a city, we’d call the places we’d highlighted in the book from a pay-phone. Inevitably one had a room.

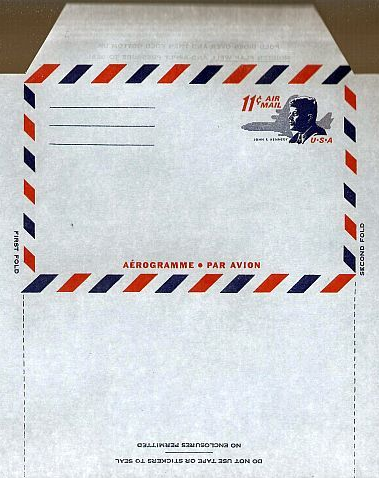

Communication home was extremely different because we could not afford long distance calls so we wrote exhaustive letters on wafer-thin paper air mail fold-up envelopes. In Paris, another student told us about a broken pay-phone that allowed anyone to call long distance. We thought we’d won the lottery when we found that phone and it actually worked. We alternated calling our friends and family for hours.

What I’m realizing as I write this column is I don’t have to give the contemporary examples of how it’s different because they are so obvious. Simply the recollection of how we traveled brings us back to a significantly different mode of getting around.

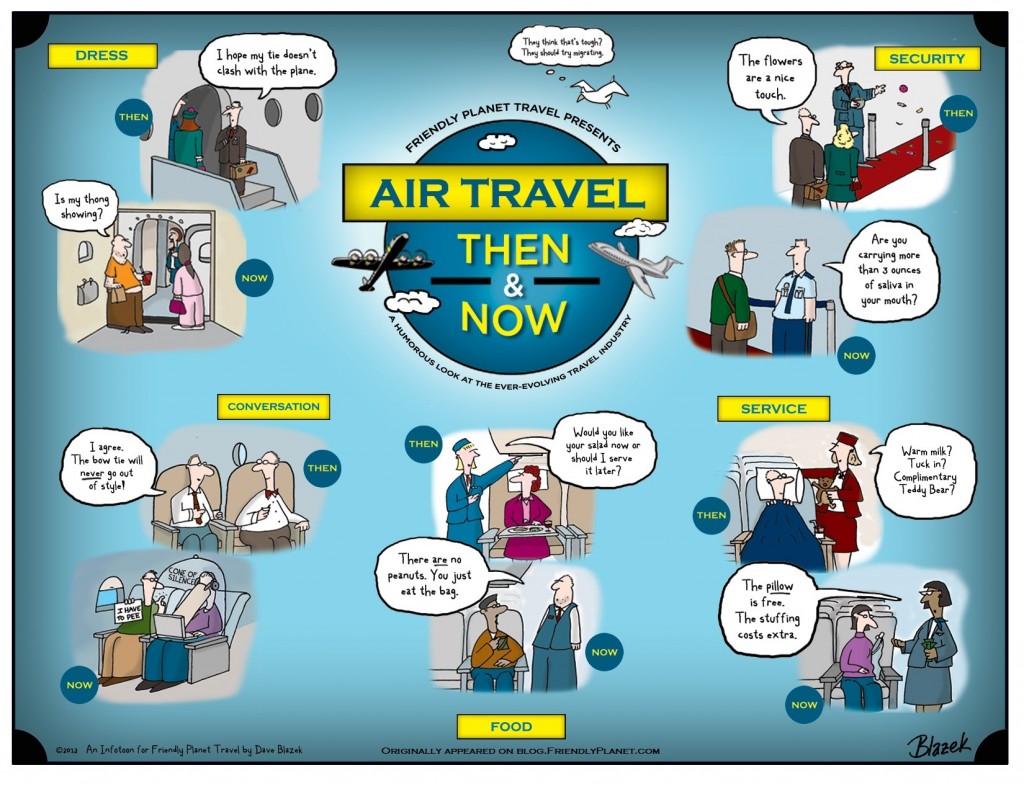

Fast-forwarding to the eighties, when I worked at ABC Television, I now was able to travel literally first-class. That meant first-class seats on planes, which, in those days, were seriously First-Class. For a short while, MGM operated extra fancy “first class” only planes and those flights were absolutely magnificent. And, once during the filming of a television series in Europe, I did a three-day turnaround from London via the now grounded Concorde supersonic jet. That was an awesome experience.

I loved those expense-account trips. I loved getting hotel suites in New York and Paris. I loved having a direct dial phone line installed in my hotel suite in Rome because I had to make so many calls that doing so via the hotel operator was simply prohibitively expensive.

Those days are long gone. Even when I flew coach – post ABC – the flights were rarely crowded and I could stretch out on a row of seats and sleep comfortably on overseas trips. The airports were pleasant. Baggage was easy. Crowds were virtually non-existent except for the obvious busy travel periods.

For nearly a decade, when things began to change, I just didn’t want to take a “big trip” anymore. It seemed every aspect of travel had become less fun. Since re-marrying, my wife takes care of our travel plans and I’ve enjoyed travel again though every airport/flying experience is a test of will for me since I have little patience and I’m slightly claustrophobic.

Professor Weber and I stayed in touch throughout the years mentioned above. Mostly we communicated via the afore-mentioned airmail letters but, later, we got in the habit of exchanging audio tapes in which we’d do a sort of question and answer with a small number of tapes. I’d play a tape received from David on my car cassette player and answer and respond to things he said on another tape with a portable tape recorder. Wow.

And, with that, I will turn over this column to Professor Weber!

Until I was about 20 years old, I had no real interest in international travel. In college I once observed to a classmate that many of our peers had dropped out to travel in Europe. “I would never do that,” he replied, “I understand there’s no showers, not even cold ones, in Europe.” Well, that did it for me! Any place I couldn’t start the day with a hot shower, I did not want to visit!

Then, not long before Bruce went to Europe, I happened to read a novel called

The Drifters. It recounted the adventures of a multinational group of twenty-somethings roaming in and out of each other’s lives traveling in Europe and North Africa. I decided I too would go to Europe—showers or no showers!—because the gritty, rambunctious escapades in the novel appealed to my inner adventurer. When Bruce came back with a glorious Europe slide show (and in those days, this meant not PowerPoint, but a set of transparent color photographic slides), I couldn’t wait to hit the road.

So I decided to drop out of college and cross the Atlantic. Surprisingly, my parents gave me their blessing (especially since I had saved money for years, to use for something as big as this, and I wouldn’t have to rely on them financially), after extracting two promises from me. One, that I would one day finish college. Two, that I would complete some sort of formal academic experience in Europe. In those days, international study opportunities did not abound. They do today, however. For example, at the university where I teach, our Office of International Programs sponsors one-and-two semester programs at over 120 universities outside the U.S.A. Throughout the year, on school breaks and over the summer, that office coordinates dozens of shorter-term study-abroad program (I myself escorted students on a two-week trip to Spain in 2011. Next year, I will teach at Swansea University in the UK on an exchange program, and must take about two dozen students with me).

But at my undergraduate university, in the early ‘70s, you had little opportunity to study abroad unless you had the very high grades required to compete for the handful of spaces available at the one or two dozen partner universities overseas. My grades didn’t qualify me. One day on campus, however, an obscure handbill caught my eye. It advertised a two-month program (about $500 for tuition, room and board) in Oxford in Shakespeare and Elizabethan drama. Majoring in English, with a special interest in Shakespeare, I had just found the formal academic experience my parents required! So I signed up, strapped on a backpack and flew to Europe, spending many months there on either side of the Oxford program. My travels in Europe changed my life as nothing had up to that time.

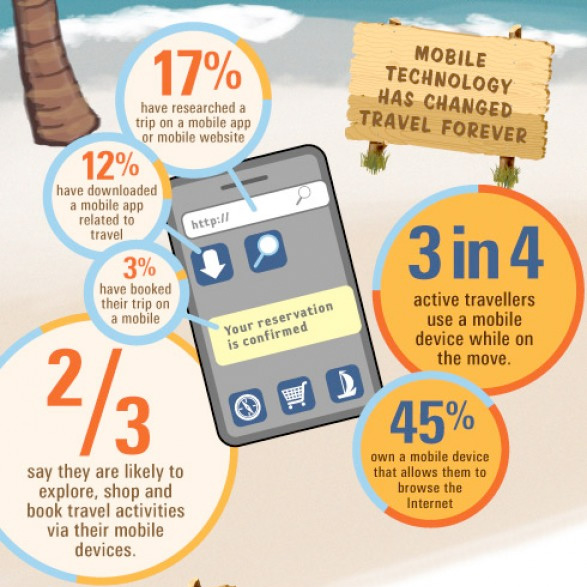

But we must talk about technology in this column. So let’s begin with current conditions: I am writing this during that England trip Bruce mentioned. I am checking email, putting out a couple of fires burning five thousand miles to the west.

But that’s little more than what happens every day in globally distributed teams. So let’s focus on the impact of technology on travel by reflecting on the task of booking transoceanic flights. Although for international air ticketing I work with a travel agent, I could choose to access this website or that and, in minutes, purchase an air ticket with a credit card. In contrast, to buy the round-trip ticket for that first trip to Europe, I drove 100 miles from my university to a student travel organization in Los Angeles to arrange for my flight. I paid a few hundred dollars in cash.

In 1994 I visited Australia and New Zealand for a few months. In a mountain town 50 miles north of Sydney, returning to my hotel one evening, I suddenly thought I would call my parents to tell them all was well. I stepped into a convenience store, purchased an international telephone calling card, found a pay phone nearby, and in a minute or two was saying hello to Mom and Dad. Some weeks later, from Wellington, New Zealand, I sent them a one-page fax to say howdy.

That convenience would be unfathomable to my 1974 self. But now, traveling abroad in the 21st century, I bring my mobile phone with me, although I use it sparingly, because of roaming charges. On my first visit to Viet Nam in late 2010, I arrived at Tan Son Nhut Airport, Ho Chi Minh City, at about midnight and texted Bruce to say hello (it was about 9 a.m. his time). This makes the phone card usage of mid-‘90s Australia seem prehistoric.

Had Bruce not found that broken pay phone (and, come to think of it, I believe he called me that day) in Paris in the early ‘70s, he would have likely made no more phone calls from the Continent than I did on my trip a year later. I made exactly one—to my parents on their anniversary. At the Paris PTT (Post, Telephone and Telegraph office) that morning, I reserved a phone line. I waited for about an hour or so and then the agent signaled me that the line was free and I should step into a certain phone booth. There I talked for no more than about three minutes on a tinny connection to Mom and Dad. The only other way I communicated with anyone that trip was by postcard, letter or aerogramme (a lightweight sheet of writing paper that you wrote on, folded up and mailed out, the cost of postage included in the price).

Bruce mentioned that on his first trip to Europe, he carried “Europe on $5 and $10 a Day” with him as a reference for sights to see, restaurants to visit and places to stay. I did precisely the same thing on my first trip to the Continent (The last time I happened to see a new edition of that book on the shelf, it was up to “$100 a Day.” On Amazon.com, I notice that they are selling a Kindle reproduction of the original 1950s book, titled “Europe on $5 a Day”). Prices today are high almost everywhere you roam, of course; but when I visit Europe today, I can’t help but notice that the meal that 1974 cost about three U.S. dollars is now 10 to 12 times more expensive.

Although over the years I have bought many travel guides—most recently one for a trip to Germany last May—I often find myself consulting websites for travel information even when I have a travel guide with me. I usually can wangle free wifi access, or visit a workstation in my hotel lobby, in order to consult the latest posts about restaurants, cultural events and activities, such as river cruises or hiking. Prior to the trip, I churn through websites of relevance, printing out pages to take with me on my travels. Surely more travel information exists than anyone can access and process; its abundance makes “Europe on $5 and $10 a Day” (plus “Rough Guide to Europe,” the only other budget travel guide I remember from those years) look like a scribbled note on a cocktail napkin. Yet for me, and I presume for Bruce, the book was our travel Bible, and possessed the wisdom of the ages for young men on the road.

When I think about the marriage of technology and travel, however, two developments particularly astonish me. One is digital photography. Between the years 1974 and 2008, I lived in three foreign countries plus traveled in just over thirty others. On all those travels, I used film cameras to take photos. From the U.S.A., I would carry with me what I guessed would be enough film (and worry about security X-ray machines damaging the film when scanning luggage). If necessary, I would purchase rolls of film in the foreign countries—a risky move, because in many countries, the film would be old, cracked or even partially exposed to light. Plus, film cost more overseas than back home. I would limit the number of shots I took every day, to conserve my precious rolls of film. In 1974, I took a photo of a street of whitewashed houses on the Greek island of Naxos. As I snapped the shutter, I thought, “What a work of art!” It turned out to be a bland, boring image. What had been a work of art now was a waste of a good frame of film.

Now, though, digital photography makes all of those concerns quaint, if not laughable. In 2008, I carried with me for the first time a little point-and-shoot digital camera, nothing special. I have carried that type of device on my travels ever since. As long as I can recharge it, I can shoot all the photos I want day after day. I load the camera with a 16G card and can store thousands of photos. Once I get home, I delete any snap I don’t want to retain, and then edit and enhance the ones I keep. For travelers who want to build and save a visual record of their travels, no worries about film, X-rays, cost or extra weight beyond any accessories you may wish to schlep with you.

The second development that astonishes me is the confluence of social media and sightseeing. In 1974, I gazed upon a mountain vista in Switzerland that I thought was the most beautiful natural setting I had ever seen. I took a photo of it (Just one shot—gotta conserve that film!). In addition to that single photo, I sketched the scene and wrote a thorough description in my notebook. I hoped all of this would prevent me from ever forgetting it, and enable me to describe it to friends once I had returned to the U.S.A.

Today, travelers snap photos and upload to Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram immediately so that friends and followers can experience the trip in virtually real time. In 2011, on that trip with students to Spain, we spent one day on Gibraltar. At the top of “The Rock,” looking out on the harbor and the water, the Med rippled to our left, with Africa beyond; the Atlantic twinkled on our right, and Europe lay at our feet. As we stood there, several students, appending almost identical photos, sent out almost identical Facebook updates: “Standing in Europe, looking at Africa, overlooking the Mediterranean and the Atlantic. How cool is that!”