Film Photography and Darkrooms AKA Bruce’s Guide to the Evolution of Technology and His Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby, Part Four*

With Guest Co-Author, Professor David E. Weber

Film photography and darkrooms is the topic for our fourth Evolution of Technology article. Yes, we are going to explore 35mm film and 35mm cameras though we won’t be taking a firm stand on film versus digital (photography). I am honored to again share the writing of this evolving series with Professor David E. Weber, who has co-authored the previous two on Drive-In Movies and Vinyl Records.

Professor Weber is starting this one with his distinct and amazing memories.

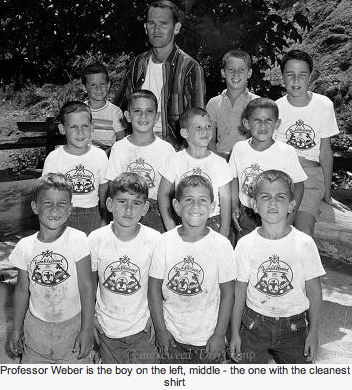

This past summer, an old high school classmate sent me a photograph (at the top of the article) in which I was one of eleven young men crowded around a blue sports car. Somehow or other, I was front and center in the shot (and it wasn’t even my car!). If I had a dollar for everyone I showed the photograph to at work, who said, “Hey, you were a good-looking kid! What happened?,” I would be packing up my office things and retiring tomorrow. Bruce Note: Doesn’t DW look uber cool in a James Dean way!

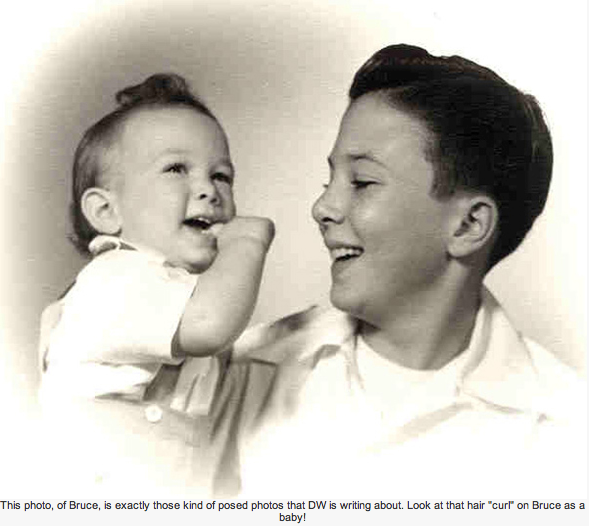

I have boxes full of other photographs that one day I swear to myself I will install in photo albums—or perhaps scan and corral in digital files. The photos document my life. I occasionally look through the photos, watching myself grow older, remembering this pivotal life decision or that dumb choice, both captured in photographs taken at those points in my life. I became the subject of photographs very early in the game—in a few of the photos, I am no more than a couple of weeks old. Several other photos were professionally snapped when I was around a year old—my mother apparently engaged a portrait photographer to pose and shoot me in our home. In one photo, I am manhandling a stuffed animal; in another, I’m balancing myself on my unsteady baby legs by gripping a chair leg.

Very few equivalent photos of my parents exist. I have plenty of photos of them after they were married (including many snapped before I was born) and several of them as single twenty-somethings, but probably no more than about a dozen or two of them as youngsters. One reason must be that starting with the first mass-market box cameras and roll film manufactured and marketed by George Eastman initially in the late 19th century, the basic tools of photography became increasingly cheaper and easier to use. By the time I was born (1952), cameras and picture taking had become staples of middle-class “baby boom” life.

Cameras fascinated me when I was a youngster and I enjoyed having my picture taken. I liked to pose in costumes—dressing like a cowboy or a soldier or, at one family garden party, like a chef, with a massive (for my size) chef’s hat and an apron that reaches my ankles. At family events, one somewhat odd uncle (every family has one) always volunteered to take the obligatory team photo—so I have many photos of my extended family, growing and shrinking in size across the years.

I remember my first camera: a Kodak Brownie. One could buy a flash attachment for the Brownie but I didn’t have one. So I could take pictures only in daylight. My next camera, a gift at about age 11, was an Instamatic 100. I kept that camera through my college years. I took few photos, though, except during summer, when I recorded family vacations, summer camp adventures and, later, my own trips with friends. I received a Polaroid Swinger as a Bar Mitzvah gift. With it I could take “instant” photos—the prototype for, today, taking a photo with your mobile phone and uploading it in a few seconds to your Facebook page.

In 1982, I moved to Indonesia. Inspired by the jungle settings and unique visual stimuli where I lived and worked, I decided to get serious about photography. On a business trip to Singapore, I purchased my first 35-mm, single-lens reflex camera. It was manufactured in the Democratic Republic of Germany (known back in the day as East Germany) and had no automatic functions whatsoever. I figured that if I had to make all adjustments manually, I would learn the basics of photography more easily.

I don’t think I’ve ever had a possession that led to more teasing than that camera did! Whenever I pulled it out to snap photos, someone would make a wisecrack—one I remember was, “Hey, Dave, how much did Fred Flintstone ask for that camera?” Back in the U.S. in the late 1980s, I set my trusty Communist camera on a closet shelf, intending to get something more contemporary. I never got around to that, however, and thus began a period in which I took very few photos. The photos I have of my life between 1988 to 2000 or so were taken by someone else.

Digital photography has been a blessing for me because you can shoot and shoot and then just delete what you don’t want to keep. Most of the photos I take tend to be taken when I travel, but I have a couple of cameras and one is usually close at hand. The camera I use is a simple, pocket-size, all-automatic camera—nothing fancy. I attempt to make up for the lack of sophistication of my camera with attention to composition and lighting. Also, I remember a quote I read attributed to Robert Capa, a great twentieth-century photojournalist: “If it’s not good enough, you’re not close enough.” So…stand close, compose well, take several shots if you can, so that you can discard the worst and keep that one gem—that’s my theory of amateur photography!

Wow, DW, those are great memories. Naturally, as you are my personal “hard drive,” I don’t have such vivid memories though I do have some that I’ll share. My first reaction, however, is to remember that fact that the cost of film was a big deal so I always was conscious of how many photos I took due to the cost of film, and it did inhibit my picture taking. That is one of the miraculous changes with the advent of digital photography in which “film” is indeed cheap. It certainly has changed how I now take pictures.

My major memories of film photography revolve around my best friend in high school, whom we’ll call Marvin for the sake of his privacy. We were always the odd couple since he was the one who knew how to do everything and I was the one who did everything crazy but didn’t know much. For years, this worked to our mutual benefit.

Marvin built a darkroom in his garage. Yeah, he built it. I can’t put together an Ikea purchase yet my high school friend somehow seemed born and gifted with a never-ending number of these sort of craft skills. As best boy-friends do, we got absolutely absorbed in whatever it was that was our interest of the moment.

So, when we weren’t playing “Tip-In” (a basketball game), we were experimenting in his darkroom. We could only take Black and White pictures and the whole process was fascinating to me. The care with which he made sure there was NO light coming into the darkroom. The various chemicals, clothespins used to hang the wet developed pictures, and the techniques we used to improve or alter photographs. There was one that involved moving our hands over the light, when a picture was exposed, and this would cause a certain effect and darned if I can’t remember what that was called? Shadowing?

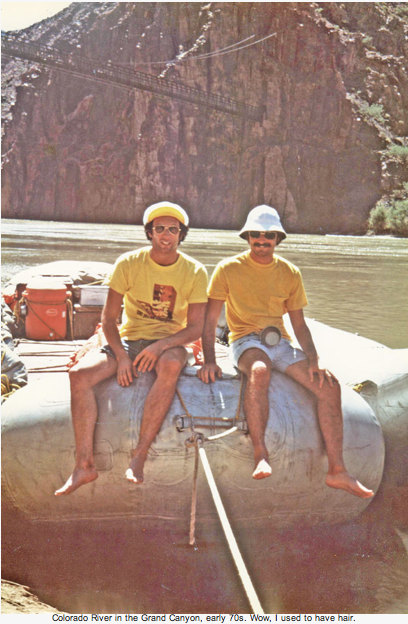

We went on photographic expeditions. Being relatively nerdy guys, we even convinced one of the “hot” and “cool” girls at school to pose in a bathing suit for us, on the top of a building. We also took photographs of each other skiing and some great ones on our river-rafting trip down the Colorado River in the Grand Canyon. And, when we traveled through Europe, back when you could use Frommer’s “Europe On $5 a Day” book (we actually used the updated edition that was $5 and $10 a day), we took extensive slides. All of which are packed in boxes in my garage. The only time I see any of those photographs is when I find the few we printed in frames in other boxes.

We never did get to do our own color developing. It was just too expensive and too difficult, according to Marvin. But, I sure loved those hours in his darkroom and I was convinced we were the next Alfred Eisenstaedt.

The next article in the Evolution of Technology series will be on “The Telephone.” Stay “dialed-in!”

* an homage to Tom Wolfe’s first collected book of essays, published in 1965.